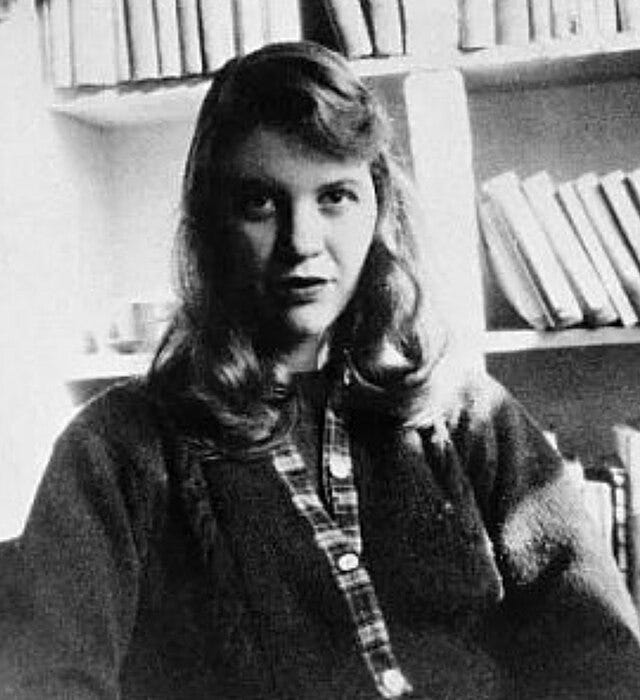

Who is Sylvia Plath?

For those who don’t know, Sylvia Plath was one of the most prolific poets of her time. With a genius level IQ, she crafted timeless work that are still some of the most celebrated poems ever.

But genius alone isn’t enough to write good poetry, or to write well at all. Something else altogether gave her the tools to be considered one of the greatest 20th century writers: her journaling habits.

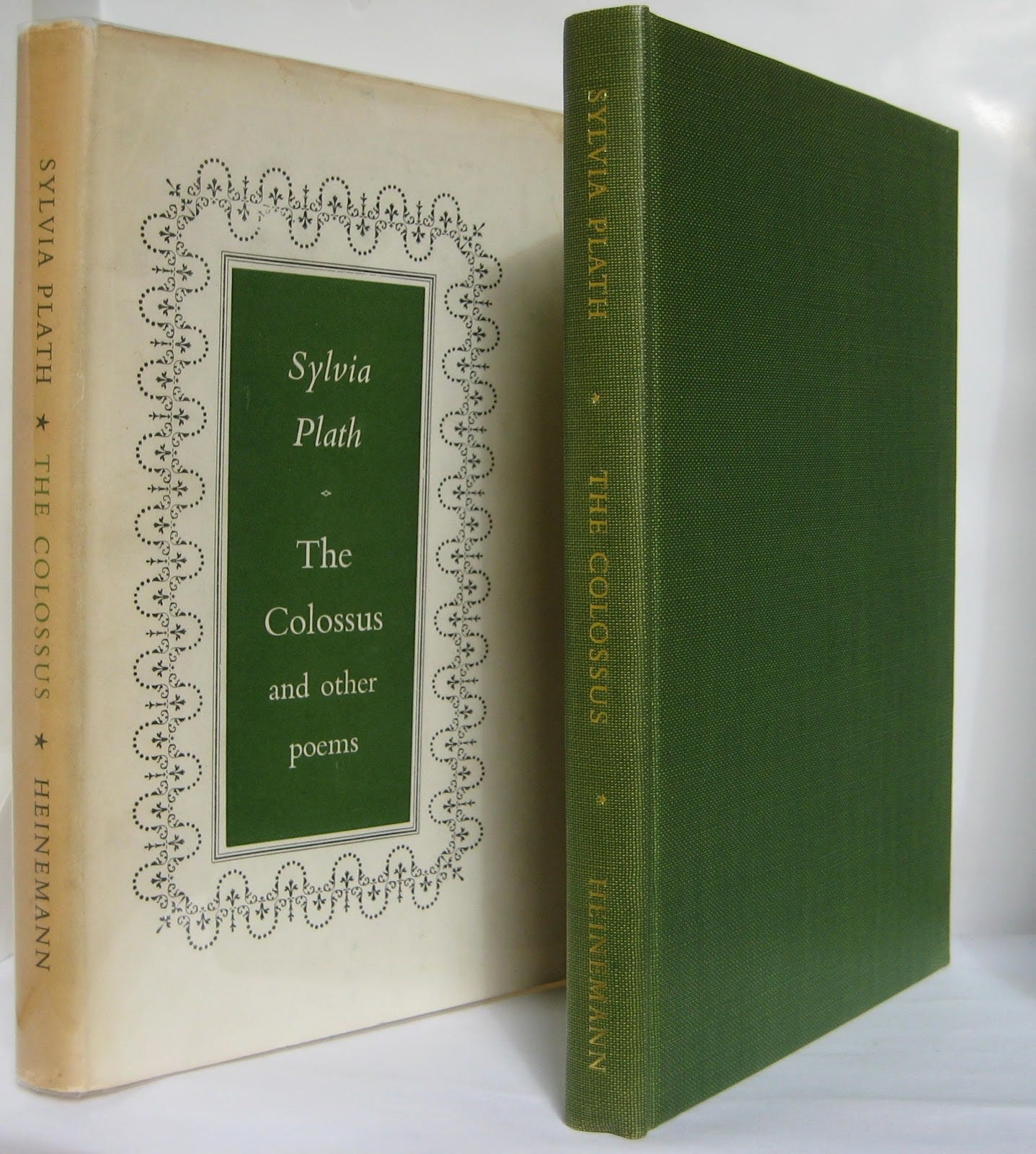

During her lifetime Plath published only one collection of poetry, The Colossus, and one novel, The Bell Jar, which she published under a pseudonym. Her most famous collection, Ariel, was written in the last years of her life and published posthumously.

Though her published work when she was alive could be read in a day or so, the amount of writing she actually did would take ages to read. Even I, a noted Sylvia Plath superfan, haven’t managed to read it all.

What Makes Her Writing Special?

Where most of her writing exists is in her notorious, and what I would consider prolific, journal keeping habits. There are a few key things that Sylvia Plath does in her journaling that led to her remarkable career and success. Concisely put, these are:

Writing often: She kept a near daily journal from the time she was five.

Writing well, and intentionally: Her entries are often well-constructed, lucid, and she almost never writes any fragments.

Pulling from her journals to write professionally: Many journal entries can be seen in her poems, and especially her novel (which was semi-autobiographical).

Focusing on these three aspects of your own journaling can help make you a better, more consistent, more observational, writer.

Writing Often

Sylvia wrote her first poem at age 5, the same age she got her first diary. The poem is called Thoughts, and boy, oh boy, is it remarkably cute.

When Christmas comes, smiles creep into my heart.

I’m always happiest when I’m singing a song or skipping along.

Obviously, most of us didn’t keep diligent journals from the age of five. Writing that young is a huge advantage. However, it is never too late to start. I just started journaling recently, and I’m nearly thirty. The only difference between me and five-year-old Sylvia Plath is that I have to try a little harder to build the habit.

While we can’t make up for our late start to journaling, we can make up for in frequency. Plath wrote most every day of her life. And you can, too.

Writing Professionally from Journals

When I was doing research for this article, I was struck to recognize so much of her journal entries. Had I read these before? Why was this so familiar? And then I realized: She is pulling inspiration from her journal.

When she was eight years old(!) she wrote this passage in her diary,

“I gradually developed a love for the stormy, turbulent ocean that few people can understand. I enjoyed lying for hours in the bright, white sand, gazing at the sparkling blue-green waves bounding in on the west beach, and the silvery seagulls dipping for fish on the crest of a frothy white-cap before it broke and washed among the pebbles. I speak so much of the ocean, because it was an important part of my heritage and environment, and my love for it is hard to explain.”

Parts of her short story, The Green Rock, written in 1949 (9 years later), borrow heavily from this passage:

“Something within her soared at the sight of the cloudless sky and the waves washing on the shore with a scalloped fringe of foam…As she stared out at the ocean, she wondered if she could ever explain to anyone how she felt about the sea. It was part of her, and she wanted to reach out, until she encompassed the horizon within the circle of her arms.”

Writing Poetry from Journals

Here is a direct pull from her journals to her poem: In a journal entry dated Monday, March 9th, 1959, she writes,

“A clear blue day in Winthrop. Went to my father’s grave, a very depressing sight. Three graveyards separated by streets, all made within the last gift years or so, ugly crude block stones, headstones together, as if the dead were sleeping head to head in a poorhouse…I found the flat stone, ‘Otto E. Plath: 1885-1940’, right beside the path, where it would be walked over. Felt cheated. My temptation to dig him up.”

Not only is this perfectly illustrative of her “writing intentionally” (which we’ll look at in the next section) but this passage shows up in her poem Electra on Azalea Path, published a year later in Harper Magazine, March 1960.

The lines reappear in stanzas 2 and 3 of the poem:

I found your name, I found your bones and all

Enlisted in a cramped necropolis,

Your speckled stone askew by an iron fence.In this charity ward, this poorhouse, where the dead

Crowd foot to foot, head to head, no flower

Breaks the soil. This is Azalea Path.

Writing Intentionally

Writing intentionally is perhaps the most critical distinction between how Sylvia Plath journals, and how many others, perhaps most others, journal.

Plath is always, always, always trying to get the most out of her experience. She uses a lot of adjectives, a lot of descriptive language. You’d be hard-pressed to even find a moment in which she uses a sentence fragment.

It’s almost as if she is writing a first draft for things to use later. Here is a section from her personal journals dated March 9, 1958—closer to the end of her life, when she was already a very prolific author. But the quality of it is very illustrative.

“Something got me in its grip these last three afternoons. Today, too, I slumped into bed, unable to hold my head up after lunch, and slipped into a sick stupor of sleep. A mild March day with an edge of cold hid in wind-stir, in the angle of shadow, a dazed squirrel hopping ungainly, half out of its hide, shoulders molting and its furry haunches. A thin green-yellow wash of light underlying bare ground, bare trees, warmly luminous and promising. O how my own life shines, beckons, as if I were caught, revolving, on a wheel, locked in the steel-toothed jaw of my schedule.”

This is just perhaps the most insane way to say, “It’s a spring day and I have a lot of things to do.” And just for clarity, Plath doesn’t normally talk like this—you can hear her in interviews speaking like a regular human person.

This entry just goes to show that she is treating her journaling very seriously; she’s treating it like practice, like a craft. Journaling intentionally is something that sets her apart not just from other people who journal, but from other poets as well.

What We Can Learn from Plath

Obviously, this is a lot of reading, and long-winded quotes from journals to illustrate my point. You need not remember the quotes exactly, or even my commentary on them. Just remember:

Write often.

Write intentionally.

And use your journal to help you write professionally.

Journaling is, of course, a pretty personal endeavor. But if you treat it with just a bit more seriousness, treat it as if you may get famous enough one day that people everywhere will read it, you can improve tremendously as a writer.

Thank you for reading! I’ll leave you with one of my favorite Sylvia Plath quotes (which she originally wrote in her journal!):

“And by the way, everything in life is writable about if you have the outgoing guts to do it, and the imagination to improvise. The worst enemy to creativity is self-doubt.”